Nicholas Molnar, an underrated hero of modern Napa wine, dies at 94

Nicholas Molnar, a winemaker who helped launch fine wine in the now-famous Napa County region of Carneros, died Jan. 11. He was 94 years old.

A Hungarian-born who fled Budapest after the failure of the 1956 revolution to overthrow the Stalinist regime, Molnar was an entrepreneurial winemaker, planting numerous vineyards in Napa County in the 1960s and 1970s. he purchased 100 acres of land in what was then considered the marginal southern part of the county, adjoining the marshes of San Pablo Bay. The climate there was considered too windy, too cold, too extreme for good wine. Today, Carneros is recognized as one of the best places in California for wine grapes, and this vineyard has become the foundation of the Molnar family’s Obsidian Wine Co..

“He was always an explorer,” said Arpad Molnar, his son.

Molnár Miklós was born in Budapest in 1927. He grew up in politically difficult times, as Hungary faced the Great Depression, then World War II, and then Soviet occupation. Molnar’s father was a business owner – he ran a trucking business – and in the late 1940s, like many who were vilified as capitalists, both father and son spent time in prison.

He married a gymnast, Andrea Bodo. While she was in Australia to participate in the 1956 Olympics, a revolt broke out in Budapest against the Soviet regime. Molnar participated, taking to the streets in October 1956. When it became clear that the Soviets would crush the revolution, Molnar fled, crossing the Austrian border alone. He found his way to Melbourne, where he was reunited with his wife, who had won a gold medal.

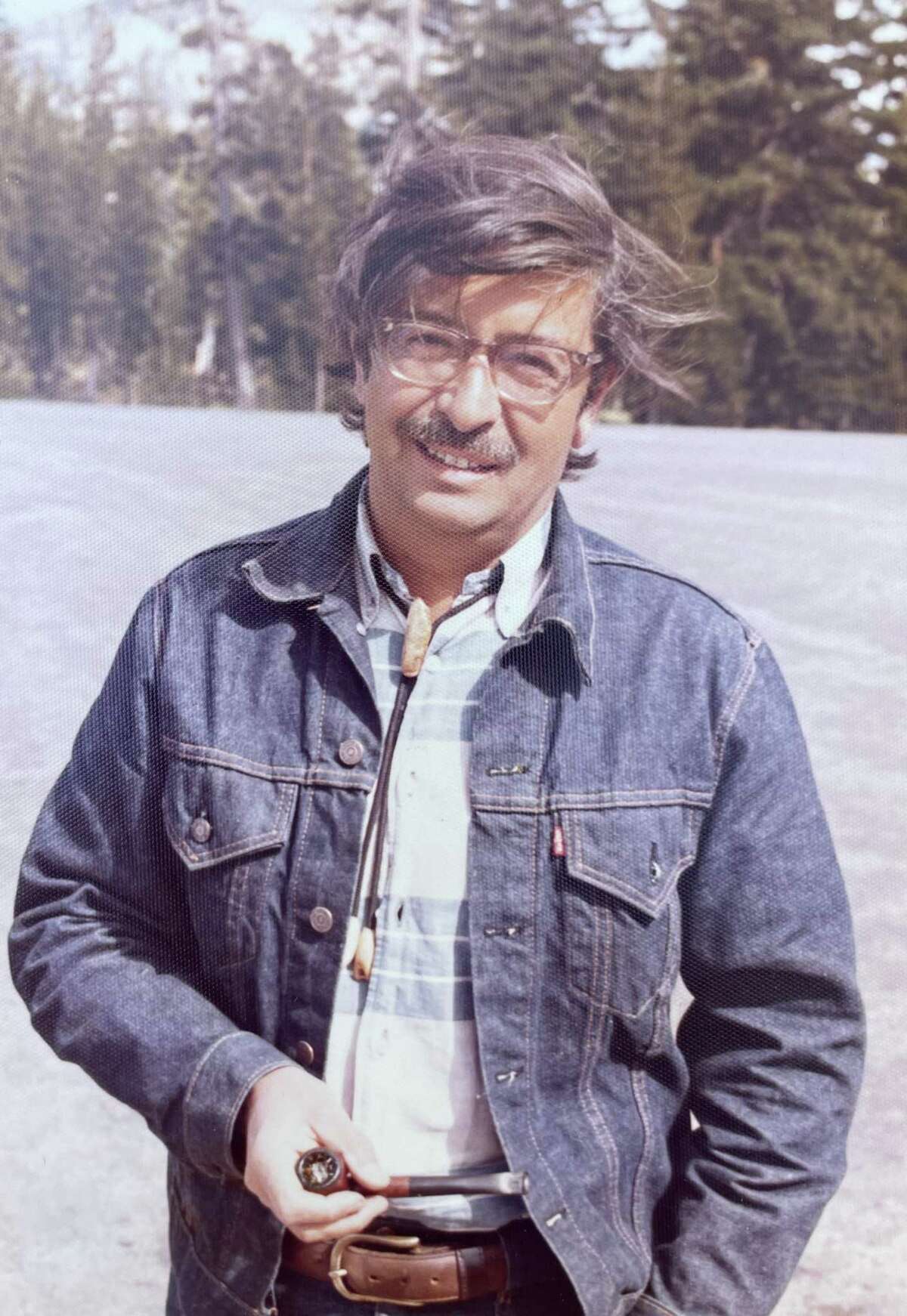

A diary photograph of Nicholas (then known as Miklos), who fled Budapest for Australia, where his wife had recently won a gold medal in gymnastics at the 1956 Olympics.

Provided by the Molnar familyMolnar, Bodo and other members of the Hungarian Olympic gymnastics team decided against returning to Hungary, initially staying in Australia. A new opportunity soon presented itself: magazine magnate Henry Luce, who had just founded a new publication called Sports Illustrated, offered to host the Hungarian team on a tour of the United States. (The move, Arpad Molnar believes, was politically motivated, publicizing refugees from a communist regime at the height of the Cold War.) The arrangement proved particularly beneficial to Molnar, who had worked as a journalist in Hungary and had been assigned to cover the tour for Sports Illustrated.

Just before Christmas 1956, the tour landed in San Francisco. “Governor. Knight Hails Stateless Group,” reads the headline of The Chronicle on Dec. 25. Molnar and Bodo immediately drove to town and decided to stay.

In San Francisco, Molnar worked briefly as a journalist, then sold life insurance. He and Bodo divorced and in 1967 he married another Hungarian refugee, Catherine de Bokay. They settle in Piedmont.

Among his life insurance clients were the Pepi brothers, who had a winery in Napa. (Originally called Robert Pepi Winery, it’s now Cardinale, owned by Jackson Family Wines.) It was here that Molnar got the idea to plant a vineyard, according to his son. He placed advertisements in the newspapers to find investors.

Nicholas Molnar, a pioneer winemaker in Napa and Lake counties, has died at age 94.

Provided by the Molnar familyBeginning in the 1960s, aided by numerous investors, Molnar purchased several undeveloped plots of land in Napa County and planted wine grapes there. Not all worked out, and in several cases he had to sell the properties to meet his obligations to investors.

But one patch, at the southern end of the county where the Napa River meets the bay, he managed to keep.

Before Molnar bought it in 1973, the 100-acre site was a pasture for sheep. Few other vineyards existed in Carneros at the time; it would be another 12 years before Carneros was officially recognized as an American Wine Country, the government designation for a wine region. Conventional wisdom held that it was not as well suited to wine grapes as the rest of Napa County.

Molnar proved otherwise. He planted Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, grape varieties that thrive in cooler climates. That same year, French champagne company Moet Hennessy arrived in Napa, intending to establish a winery – what would become Domaine Chandon – and was looking for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, the grapes used in Champagne. Until 1985, Molnar sold the entire harvest from his vineyard in Chandon. Today, the fruit is sold to sparkling wine producers Schramsberg and Mumm, and also used for the Molnar family’s Poseidon label.

“He was always an underdog,” Arpad Molnar said. “The wine industry is so insular, and he kind of hovered around that scene, but never wanted to be in that scene. He always thought that when you’re a little bit outside of that, you can think creatively.

Winemakers Catherine and Nicholas Molnar, both Hungarian refugees, met in San Francisco and married in 1967.

Provided by the Molnar familyIn the early 1990s, Molnar and his two sons, Arpad and Peter, became involved in efforts to revitalize the Hungarian economy after the fall of communist rule. Molnar’s first idea: wild rice. “He read an article about wild rice in the San Francisco Chronicle and how popular it is,” Arpad Molnar said. So he bought some, flew to Hungary and helped farmers plant it in their fields.

He had a similar idea about wine barrels after he found a cooperage in Hungary, called Kádár, which was having financial difficulties. Although it once produced wine barrels, during the Soviet occupation it was forced to make furniture for Russian markets. Kádár “was basically on life support,” Arpad Molnar said. They decided to help by buying his barrels and importing them to the United States

“The winemakers told us that no one here will ever buy a Hungarian barrel,” Arpad Molnar said. Then as now, the California wine industry is modeled after France, growing French grapes – like Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir – and aging them in French oak barrels, which many top wineries of range still regard as the gold standard. When the Molnars imported their first Hungarian casks, in 1993, their main selling point was that they were cheaper than their French counterparts. At first, their only client was Gallo.

But again, Molnar was ahead of the curve. The Molnars now sell Kádár barrels to 120 wineries in California and countries like Australia and New Zealand. The family eventually took a stake in the cooperage, adding an impressive partner – the famous French cooperage Taransaud.

Molnar’s land in Carneros in 1973, before he planted Pinot Noir and Chardonnay there. Molnar first called his site the Chardonnay vineyard; his children later convinced him to change the name to the less generic Poseidon Vineyard.

Supplied by the Molnar family 1973Molnar’s last major frontier was in Lake County. In the late 1990s, land in Napa County was getting expensive and he suspected there was opportunity in areas just north of the county line, where the land was similar but the real estate market was strong. softer. Still with investors, he and his sons purchased a 100-acre walnut orchard in 1999. The ground was strewn with large boulders of shiny black obsidian. They called the vineyard Obsidian Ridge and quickly developed a strong reputation for producing Napa Valley caliber Cabernet Sauvignon.

“None of this hit us much later, but it was as obvious as planting in Carneros in the 1970s,” said Arpad Molnar of the Lake County project. “Everyone said you couldn’t grow a great Cabernet in Lake County.”

His father wanted to be remembered as a pioneer, said Arpad Molnar. “He had this relentless curiosity. He was always interested in what was new, not quite there yet. Sometimes it didn’t work. And sometimes it was.

Nicholas Molnar is survived by his wife, Catherine; his children Aniko, Peter and Arpad; and his grandchildren Renna, Kyla, Nichos, Gabriel, Eszter and Andreas.

Esther Mobley is the principal wine critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. E-mail: [email protected]

Twitter:

@Esther_mobley

Comments are closed.